On December 1, 1958, one of the deadliest fires in America broke out at Our Lady of the Angels school in Chicago’s Humboldt Park neighborhood, claiming the lives of 92 children and three nuns. A tight-knit faith community was changed forever by the fire, and there was a new public clamor for safer schools as a result.

On December 1, 1958, one of the deadliest fires in America broke out at Our Lady of the Angels school in Chicago’s Humboldt Park neighborhood, claiming the lives of 92 children and three nuns. A tight-knit faith community was changed forever by the fire, and there was a new public clamor for safer schools as a result.

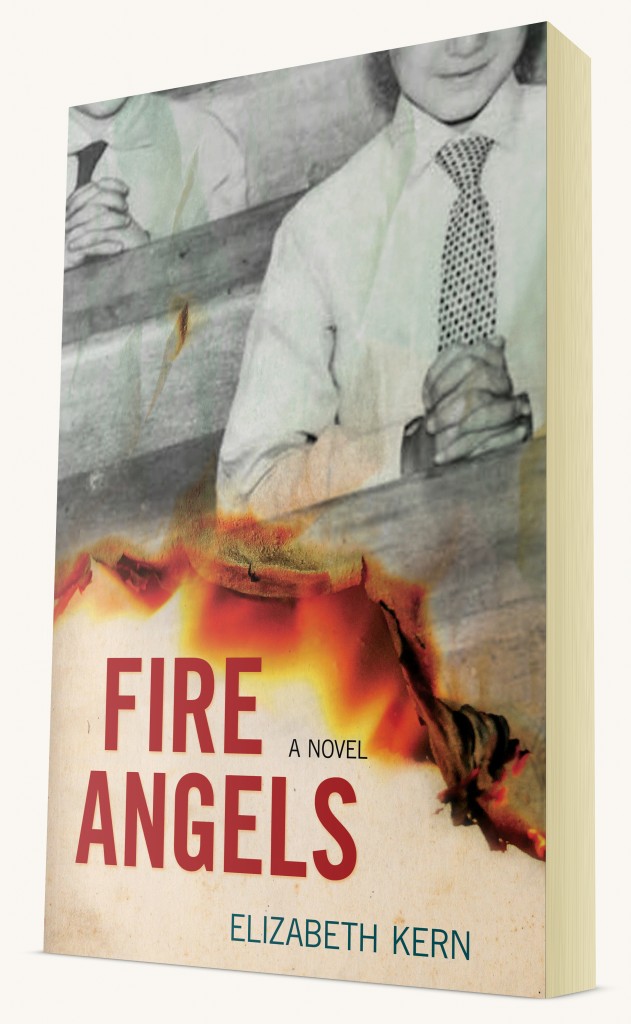

Elizabeth Kern’s new novel Fire Angels imagines the lives, emotions and in-the-moment actions of children and adults involved in and affected by the tragedy. Kern is a third generation Pole who grew up in Chicago’s Old Polish neighborhood, near the intersection of Milwaukee, Division and Ashland—about three miles away from Our Lady of the Angels. On the anniversary of the fire, she shares her inspiration for writing historical fiction, how she handled using real life characters in the story, and what she hopes readers will take away from her novel.

What inspired you to write Fire Angels?

I remembered that day—December 1, 1958— and the horror of it. I grew up on Chicago’s northwest side, and I had just returned home from school. We learned about the fire on TV. From our third floor apartment we heard sirens of fire trucks racing to OLA from all parts of the city. From our living room window we watched smoke billowing in the west. The number of fatalities kept getting higher. I identified with the children because many were my age. It could have been me. It could have been my sister and our classmates.

We attended a grade school that was much like Our Lady of the Angels in terms of age, construction, and absence of fire doors, a sprinkler system—all those safety devices we take for granted in schools today.

Back then I only knew what I read in the papers, and I read everything I could get my hands on. I remember that a janitor was held suspect. I remember images of children jumping from the windows of their second-floor classrooms, uniforms ablaze. The Chicago American ran the photos on the front page of 70 of the victims, some dressed in their Communion dresses and dark suits. Those images stick in one’s mind.

Then many years later, as I was searching for a topic for my next novel, I read To Sleep with the Angels, by John Kuenster and David Cowan, a journalistic account of that fire. I was blown away by the complexity and lingering mystery of the story, and by the depth of the authors’ research. Then I saw the story through much more mature eyes, and as a writer, it had all the ingredients of a multi-faceted novel: It was the story of one of the most horrific fires in American history. It was a story of confessed and then denied arson by a ten-year-old student; of bravery by parents, nuns, firefighters, and medical professionals; of a falsely accused janitor; of a cover-up within the Catholic Church; of a judge who, in having to determine the juvenile arsonist’s fate, is torn between loyalty to his church and justice; of a tight-knit community changed forever; and of two survivors who years later fell in love and married, at our Lady of the Angels Church.

Fire has a voice in your novel. Where did that idea come from?

That idea came pretty quickly. I thought of how Markus Zusak gave Death a voice in The Book Thief, and I thought, What if I personified Fire? From my first sentence of the book—“There was this fat-faced kid who loved me. Not the normal attraction a kid has when he sees me in the flick of a match or in a candle on a birthday cake. This kid loved me too much”—it felt right. I gave Fire the ability to speak whenever a flame was lit; in addition to the fire itself, everyone smoked in the 1950s, so I had endless opportunities.

You used a combination of real and imaginary characters to portray the Italian, Irish, and Polish residents of the neighborhood and the city and church officials involved in the fire and its aftermath. Why?

I used the real names of the priests, nuns, most of the victims, the falsely accused janitor, the judge, the lie detector administrator, and the founder of the boy’s home where the kid was “rehabilitated.”

Originally, I wanted to use the names of the two survivors who eventually married, but after some soul searching the couple decided not to participate—which I understand—leaving me to create a Plan B. In the end, I gave them fictitious names and family backgrounds, but based their stories (their injuries and marriage) upon the real couple. Ultimately this gave me more creative license in molding the characters and perhaps improved the story—at least that’s how I look at it now.

As for the ten-year-old arsonist, I chose not to use his name and refer to him simply as “the kid.” Although it’s pretty easy to find out his name on the Internet, I chose not to reveal it, giving him a sense of “otherness,” an identity that separated him from the 95 innocent lives he took and the children and families he harmed.

I didn’t know his parents’ names, but I had read facts about their backgrounds, their parenting styles or lack thereof, upon which I built the characters of Belinda and Manny.

I didn’t know his parents’ names, but I had read facts about their backgrounds, their parenting styles or lack thereof, upon which I built the characters of Belinda and Manny.

You deal with a number of religious issues in Fire Angels. What do you hope readers—Catholics, survivors, and others—will take away from the novel?

As a writer of historical fiction, I research carefully and strive for accuracy. It’s not my business to rewrite history, but to tell an interesting story within historical parameters. Writing historical fiction allows me the liberty of creating scenes and characters to support a story, and dialogue where often there is no record of it. In the case of the OLA fire, I had access to countless documents: transcripts of the inquest and the lie detector test administered to the young boy, for example. I also had access to the stories of many of the survivors kept alive on olafire.com.

As for the brave survivors and their families, and the families of the heroic firefighters and medics who dealt with the aftermath, I hope they will see Fire Angels for what it is: a story based on facts and the telling of a conflagration that changed the way American schools are built throughout the nation. I believe it’s important to keep this story alive both as a tribute to the people involved, and as a reminder to never let up on fire safety standards, especially for our children.

Elizabeth Kern, also the author of Wanting to Be Jackie Kennedy, and Mercy Goodhue: A Puritan Woman’s Story of Betrayal, Witchcraft and Madness, is a former manager of corporate communications at Apple, a native of Chicago, and a graduate of Stanford University where she developed her passion for writing historical fiction. She lives in Petaluma, California.

“The story is heartbreakingly engrossing, and part of Chicago’s living history.” —Foreword Reviews

Fire Angels officially published on November 1, 2016 and is available wherever books and e-books are sold.

[Get it now $15] [Request a review copy] [Read an excerpt on Arcturus]

1 Comment

Your portrayal of the OLA fire is very interesting to me. I was a four year old, living in a Chicago neighborhood approximately five miles from Our Lady of the Angels school and church. My mother remembers that I was very concerned and upset by the news coverage of the fire. I’ve have researched and read everything I can find about this tragedy. I am somehow drawn to this horrible tragedy. I’m sure I’m not the only person to be interested. For some reason, I feel some connection to the whole story. Thank you for your book that personalizes the terrible tragedy from so long ago.