On the eastern edge of Concord, Massachusetts, just off Virginia Road, there stands a simple white and red Georgian-style home surrounded by a quaint stone fence. It’s where Henry David Thoreau was born in 1817, and now, nearly two hundred years later, it’s where Henry David Thoreau for Kids author Corinne Hosfeld Smith gives tours as a licensed docent. She’s been educating visitors there nearly since the site opened to the public in 2010, and here she discusses her passion for the job, the highlights of the tour, and the books that have kept her knowledge of Thoreau and his birthplace sharp.

On the eastern edge of Concord, Massachusetts, just off Virginia Road, there stands a simple white and red Georgian-style home surrounded by a quaint stone fence. It’s where Henry David Thoreau was born in 1817, and now, nearly two hundred years later, it’s where Henry David Thoreau for Kids author Corinne Hosfeld Smith gives tours as a licensed docent. She’s been educating visitors there nearly since the site opened to the public in 2010, and here she discusses her passion for the job, the highlights of the tour, and the books that have kept her knowledge of Thoreau and his birthplace sharp.

When did your fascination with Thoreau begin?

It started when I read his essay “Civil Disobedience” in tenth grade and the book Walden in twelth grade at Hempfield High School in the suburbs of Lancaster, Pennsylvania, in the early 1970s. I admired his spirit of independence, and like him I loved being out in nature, so I was hooked. Then I moved on to Clarion State College to study library science. I checked out the fourteen volumes of Thoreau’s journals from the library, one by one, during my four years there. I read them and copied my favorite passages in a notebook that I still have. And this “has made all the difference,” as another famous poet once said.

How did you end up becoming a tour guide at the Wheeler-Minot Farmhouse?

After working for many years as a librarian in Pennsylvania and Illinois, I moved to central Massachusetts in 2003. I relished the idea of living only an hour away from Walden Pond. In 2006, I took a course in Concord history and became a town-licensed tour guide. Thoreau Farm, known as the Wheeler-Minot house on the National Historic Register, was then in the process of being restored. It opened to the public in 2010. I had a chance to become a docent here beginning in 2011. I also contribute to the blog for the site.

What’s the one fact about Thoreau’s birthplace that you’ve found surprises most visitors?

In 1878, well after Henry’s death in 1862, the two-and-a-half-story farmhouse was moved three hundred yards east to its current location. The farmer who owned the land wanted to board his tenant workers here. Then he put up his own new house back on the original site. It’s a startling thought, to consider a whole house being moved intact, inch by inch, and probably with the use of large logs and teams of oxen. It may have happened in winter, when snow and ice would have helped. These Yankees didn’t throw away or tear down anything valuable. Most of the boards from Thoreau’s Walden house were used in other buildings around Concord, shortly after he moved back to town in 1847.

Are there portions of the home that you’ve had the opportunity to see that visitors aren’t allowed access to?

Actually, the Thoreaus moved out only eight months after Henry was born. And when they were here, they lived only in the eastern half of the house. This is the part we show to the public. The rest of the rooms serve as the private offices of Thoreau Farm, The Thoreau Society, and Gaining Ground, the organic-farming initiative that tends the eighteen acres behind the house. But the coolest place of all is the attic. We guides often take people up there as an extra part of the tour. It’s used as a storage space now. But you can see the original log rafters and even the old wooden pegs that hold the roof together. This house was built in 1730 and was moved a century and a half later. And it’s still a solid structure. Amazing.

How did working as a docent inform your writing of Henry David Thoreau for Kids?

One fall morning in 2012, a family of four visited the house. The young daughter carried the paperback book The Fledgling, by Jane Langton, one of the episodes of the Hall Family Chronicles, for middle-grade readers. In the series, members of an eccentric family live in an equally eccentric house on Walden Street in Concord, Massachusetts. They own and talk to their marble busts of Henry David Thoreau, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Louisa May Alcott. The Halls do their best to live according to their heroes’ philosophies. This daughter must have convinced her family to come to Concord to see if the people, the places, and the magic in the stories were real. They had stopped at Thoreau’s birthplace to find some answers. I could see that the usual house tour wouldn’t be enough. As her father nodded his approval, I took the girl aside and chatted about Thoreau’s advice to be awake and aware, to be true to oneself, and more. We looked at each other eye-to-eye, and she seemed to absorb every word. I think Thoreau’s ideas made an impression on her that day. At the same time, I was frustrated. I couldn’t tell her everything in ten or fifteen minutes. And I had nothing I could hand to her so that she could discover more on her own about who Henry Thoreau was and what he did. This book would have helped both of us that day. As I wrote it, I looked into her big brown eyes once again.

What books have given you the most insight into Thoreau’s life and the home in which he was born?

One reason the family moved out was that the farming didn’t go well. Because of atmospheric ash from an Indonesian volcano that erupted in 1815, this part of the continent and northern Europe experienced the Year Without a Summer in 1816. Massachusetts had frost in every month, which was tough on farmers. The Year Without Summer: 1816 and the Volcano That Darkened the World and Changed History, by William and Nicholas Klingaman, provides this background. The Thoreaus would instead become adept at making quality pencils; and a whole chapter is devoted to them in The Pencil: A History of Design and Circumstance, by Henry Petroski. Henry additionally taught himself surveying, and you can read about this aspect in Thoreau the Land Surveyor, by Patrick Chura.

How would you say Thoreau’s works and life are specifically appealing to kids?

How would you say Thoreau’s works and life are specifically appealing to kids?

Thoreau had a childlike curiosity about the natural world. He could give full attention to even the smallest plant or flower. Today, kids have chances to get this close to nature, especially through programs at schools and local nature centers and through the “No Child Left Inside” initiatives of environmental educators. Kids are more apt to question long-standing practices like Thoreau did, too. Just because something is the way it’s always been done, does this make it right? A young person will still have the capacity to wonder and won’t just go along because everyone else is doing it. Adults: maybe yes, maybe no.

What books are you reading currently?

I just finished reading a thin academic book from the early 1970s, Thoreau Abroad: Twelve Bibliographical Essays, compiled by Eugene F. Timpe. It’s a fascinating look at how Henry Thoreau’s reputation eventually spread around the world, to people in places like the Netherlands, Australia, and other countries. Most of this didn’t happen until the mid-twentieth century. I would have referenced one of these stories in Thoreau for Kids, if I had read this book before writing that one.

Now I’m into a nearby-nature book called Circling Home, by John Lane. John wanted to explore the nature of his neighborhood in Spartanburg, South Carolina. He got a topographical map, centered one of his wife’s dinner plates over their home, then traced around the china. The result was a two-mile-wide circle that could act as a local guidebook for exploration. I love this idea. I don’t think you have to go far to get out and into nature. I make new and interesting discoveries each time I walk a one-mile loop around my suburban neighborhood. Of course, this follows what Henry Thoreau did in Concord, too. As a matter of fact, John Lane begins his book with a Thoreau quote. There’s no escaping him.

-compiled by Geoff George

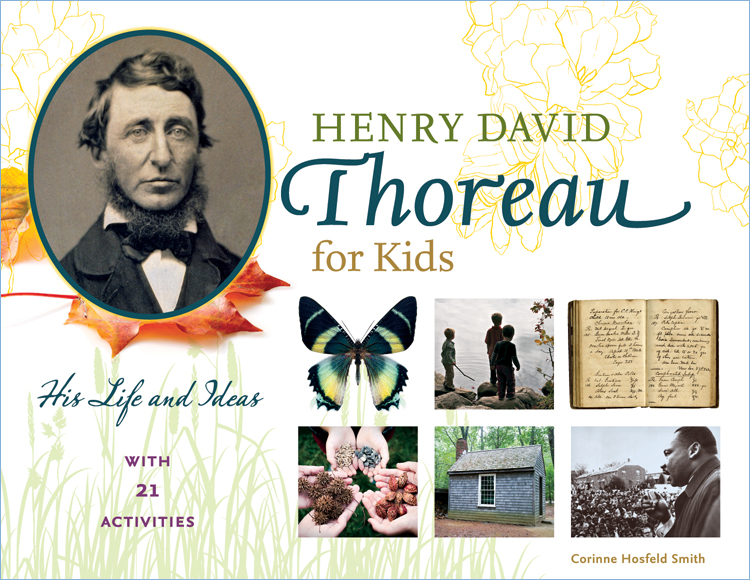

Henry David Thoreau for Kids officially publishes on February 1, 2016. It will be available where books (and e-books!) are sold.

1 Comment

Great and insightful interview! Oddly, many do not connect the (several years of) volcanic activity with the Thoreaus leaving the farm, but you’ve got it bang on. Congrats!