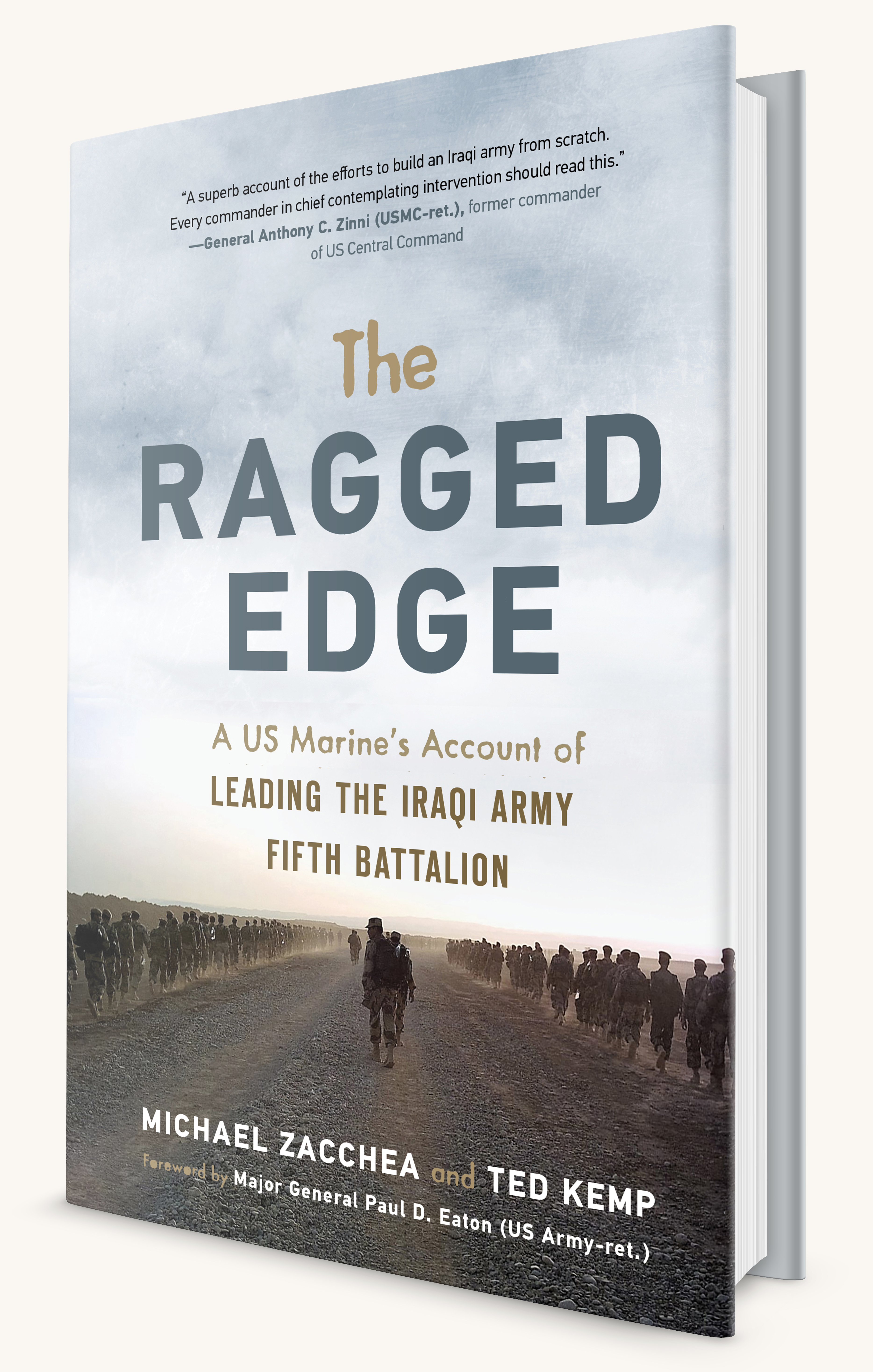

Lt. Col. Michael Zacchea, USMC (ret.) and Ted Kemp, senior editor in charge of CNBC Digital’s foreign desk collaborated to tell Michael’s story of his time in Iraq in The Ragged Edge: A US Marine’s Account of Leading the Iraqi Army Fifth Battalion. Cinematic and gripping, his deeply personal narrative sheds light on how the United States and the Middle East got to where they are today and explains the dangerous pitfalls of training foreign troops to fight determined, murderous insurgents. At this time when the United States is trying to decide on how deeply to involve itself in Iraq and Syria, Michael Zacchea holds a unique vantage point on our still-ongoing war that is shared by no one else, anywhere.

Could you describe the process of writing The Ragged Edge? Had you both discussed the content of the book before you began working together?

Michael Zacchea: It took a long time to write. It came out of two sources, 1) the NYU Veterans Writers workshop which I attended in 2006–2007 and 2) cognitive behavioral therapy that I did in 2008–2009. I wrote the first notes about the book – my very first ideas – on hotel stationery one sleepless night. I still have those notes. When I finished the CBT, I had over 300 pages of hand-written material.

The writing was in fits and starts, and episodic. I was going through my own stuff. But we kept working on it. January 2014, when ISIS captured Fallujah, was a real turning point for me writing. That sort of threw gasoline on the fire, so to speak. We finished the manuscript 18 months later, in August 2015.

Ted Kemp: One of the first things Mike expressed to me when we first met was that it frustrated him—angered him, really—that Iraqis were never humanized in American books, American movies, you name it. So that was an early part of our mission. From the beginning, we knew we were creating a book about cultures colliding as much as we were writing about armed men clashing.

The reporting was as challenging as the writing. I interviewed dozens of guys about their experiences. I read through Mike’s journals and the 300 pages he had written as part of his therapeutic efforts. The trick was figuring out the chronology—which is necessary for figuring out causality—and then also placing a larger political and historical overlay on top of those personal narratives. Most people don’t talk about their experiences or write about them in a neat, orderly way. So for me it was like gathering up a million splinters and trying to reform them back into this one, whole story.

Mike had kept detailed notes and journals—he even had jotted down quotes from people, which blew my mind. The scene in The Ragged Edge where General Eaton gives his speech in the Green Zone, for example, all of that is verbatim. And then of course Mike’s therapeutic writing was indispensable. He had poured detail onto those pages, and they came straight from his heart. I told Mike right at the beginning, if this book is going to be a success, it’s going to have to expose your mind and your feelings.

Our actual writing process was one of perpetual back-and-forth. I would write something, and I was always going back to Mike: Is this right? Is that right? What were you feeling at that moment? What were you seeing or hearing or smelling at that moment? And even the writing process itself would jog Mike’s memories about things. Our goal was to make it personal, to make it intimate. Mike and I were perpetually filling out the details, the edges of the image, in our effort to make it a lived, psychological experience for the reader. We had to do that, and then it also had to be true.

What was the best part about writing this book?

MZ: This project was therapeutic for me. It was a confluence of my own therapy, and of geopolitical events as ISIS asserted itself in Iraq. Between writing out my experiences, many of which were not included in either the published body or the submitted manuscript, and the work Ted did in interviewing the people, and reviewing all the source material, I found it very very helpful to develop the whole picture. Relationships, themes, and plots that were not apparent to me when I was experiencing it became apparent, and explained a lot.

TK: It looked so impossible at the beginning. Slowly, I got command of this year that happened in Iraq from February 2004 to February 2005—a year for which I was not present and was learning about entirely second- and third-hand.

And then sometimes Mike would say to me, “Wow, yeah, that nails it.” Not always, or even most of the time, but sometimes, on the first go ’round. I got to where I trusted my judgment. That felt good.

Michael Zacchea with Zayn al-Jibouri (left) and Abdel-ridha Gibrael (in beret), at Kirkush.

Michael, you developed a friendship and a tight bond with Zayn al-Jibouri, the battalion’s logistics officer. Do you still keep in touch with Zayn?

I did keep in touch with Zayn until July 2014. I heard from him after the fall of Mosul, as we write in the final chapter. I have not been in contact with him since. I pray for his safety and for his family.

What is the biggest misconception people have about the US’s involvement in Iraq?

MZ: Oh Geez! There are still people who believe, who ask at every speaking engagement:

1) Saddam Hussein was behind the 9/11 attacks – He wasn’t!

2) That Saddam Hussein had either weapons of mass destruction, or a program to produce WMD – He didn’t!

3) ISIS or Al Qaeda already existed in Iraq before we invaded – FALSE!

4) That either President Obama or Hillary Clinton founded or supported ISIS – FALSE!

5) Why was I helping the Iraqi Army, if they were the enemy – LONG STORY, READ THE BOOK!

6) President Obama pulled the US out of Iraq too soon. In 2008, Iraq was a sovereign government. US forces were in Iraq under legal authority of a Status of Forces agreement. The US pulled out of Iraq according to the timeline agreed to in the Status of Forces Agreement by the Bush administration in 2008.

TK: That it started a war that ended. Americans look at the Iraq War and the Syria War as two wars, but they’re one war. That war is ongoing. Aleppo is the latest extension of a war that began in 2003. There are not as many Americans on the ground as there used to be, but the salient truth is that it’s one war, and it includes more and more people all the time.

Michael is the first Western serviceman since Lawrence of Arabia to train a Middle Eastern army for combat. Were you both pretty familiar with T. E. Lawrence before writing the book? I noticed you included a quote from him at the beginning of the book.

MZ: I was extremely aware of Lawrence. I had read and studied him extensively during my career, going back to my days in college. I had read several times Lawrence’s Seven Pillars of Wisdom, and was also very familiar with his earlier 27 Articles. While in Iraq, I re-read SPW. I also re-read it since I’ve been home.

While in Iraq, I also read, The Arab Mind by Pitai, Riding the Waves of Culture by Trompenaars, A Modern History of Iraq by Phebe Marr, A History of Iraq by Charles R. H. Tripp, Kanan Makiya’s Republic of Fear and Cruelty and Silence.

We also read The Village by Bing West, 1776 by David McCullough, and How We Won the War by Vo Nguyen Giap.

TK: Yes, definitely. I was already sort of in awe of Lawrence, who had this combination of fearless nonconformity and surpassing brilliance. Then Scott Anderson’s book Lawrence in Arabia came out in 2013, and I read it immediately. Anderson evoked very big themes and yielded insights about the very nature of the Middle East and the Western world, all through the intimate story of one guy. It reinforced this idea in my mind that Mike’s story did the same thing about the Iraq War. Before that, I was inspired in the same way by Neil Sheehan’s A Bright Shining Lie, in which Sheehan found this one guy, John Paul Vann, whose personal story brought out all of these much larger truths about the Vietnam War, and about the Vietnamese people and about Americans. I read that book before I met Mike, and I read it again while I was working with Mike. Both of those books told history more effectively than straight history books do.

Michael, you recently wrote an op-ed on CNBC regarding President Trump’s executive order banning immigrants and refugees from several Middle Eastern countries. Obviously, The Ragged Edge is incredibly relevant to the new administration. If politicians were to pick up your book, what part of the book would you recommend to them and why?

MZ: Politicians have been inoculated from the consequences of the wars. Politicians have further inoculated the American people from the consequences of war by “outsourcing” fighting to third-country nationals.

The prevalence of private military contractors is a massive problem. This was part of the so-called Rumsfeld doctrine. Essentially, the Rumsfeld doctrine was the privatization and outsourcing of war for profit by a select group. The military has virtually no control or jurisdiction over contractors in country. Every federal agency is putting out different contracts all with different and uncoordinated statements of work. And as we pointed out, it leads to absurd situations like military personnel being guarded by private guards–and not guarded well.

The use of contractors is what led to the first and second battles of Fallujah. The use of contractors also led to the Al Nissor Square massacre, in which 17 Iraqis civilians were killed by 5 American mercenaries in September 2007. The Iraqi government was rightly outraged and demanded justice. As part of the negotiations for the SOFA, the Iraqi government insisted (nonnegotiable) that American troops be subject to Iraqi, that is, Sharia law as a condition for being in the country. The US Bush administration refused.

Finally, the book is incredibly relevant to both our domestic politics today and the ongoing war with ISIS. The Trump ban initially failed to acknowledge or understand the Iraqi Special Immigrant Visa program for Iraqis who risked everything, and often made incredible sacrifices, for the United States.

As I write today, American troops are in combat with ISIS in and around northern Iraq and Mosul. Those troops lives are literally dependent on interpreters. Interpreters who might be caught or even identified by ISIS run the risk of them and their entire families being executed in the most brutal fashion imaginable, by ISIS. Giving those Iraqi interpreters an opportunity to come to the United States is vital to our potential success against ISIS.

What do you hope readers will take away from reading The Ragged Edge?

What do you hope readers will take away from reading The Ragged Edge?

MK: First, that everything the American public has been told about the Iraq war is by people and interests that want to reinforce a particular narrative about the war. These people and interests want the audience to believe–to buy into–a particular narrative about the war. Often, they want the audience to believe the narrative because they have a vested interest in it.

I believe that the American people deserve to know the good, the bad, and the ugly about the war. I believe that an informed electorate can make the best decision about the use of military force by the United States to achieve its geopolitical and strategic goals, and to make the best decision about allocation of national resources like taxpayer money to achieve its goals.

I believe, and have experienced, how generous and welcoming our nation is to Iraqis who supported the United States and to refugees of the war. Most Americans are not connected to either. I honestly believe that the more the American people know about the war, the less likely we are to repeat its mistakes.

TK: I want people to finish it and say, “Wow, I feel like I finally understand the Iraq War.” I hope the book gives readers a new grasp of a big part of their own era. And maybe they’ll begin to think in ways that are more broad than they’re accustomed to thinking. Americans of all political stripes could stand to think more often beyond their immediate, lived worlds. Our technology, our jobs, our entertainment, most of them reinforce myopia. We could stand to broaden our thinking, now more than ever.

The Ragged Edge: A US Marine’s Account of Leading the Iraqi Army Fifth Battalion by Michael Zacchea and Ted Kemp, officially publishes April 1, 2017. It is available wherever books and e-books are sold.

Book Excerpt [Soldier of Fortune]

A Connecticut Marine Reflects On His Mission In Iraq [WNPR]

“An honest, revealing glimpse of the dangers inherent in acting on good intentions based on ignorance.” –Kirkus

No Comments

No comments yet.