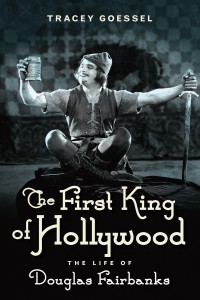

To say that Tracey Goessel is a superfan of silent film star Douglas Fairbanks may still be understating it. She has lectured on Fairbanks widely and has published numerous articles on silent film history. She’s also a major collector of silent film ephemera—she owns, for example, the boots that Fairbanks wore in Robin Hood—and her purchase of the Mary Pickford-Fairbanks love letters started an eight-year quest to write The First King of Hollywood, the definitive biography of America’s favorite swashbuckler (she relays the full story below).

To say that Tracey Goessel is a superfan of silent film star Douglas Fairbanks may still be understating it. She has lectured on Fairbanks widely and has published numerous articles on silent film history. She’s also a major collector of silent film ephemera—she owns, for example, the boots that Fairbanks wore in Robin Hood—and her purchase of the Mary Pickford-Fairbanks love letters started an eight-year quest to write The First King of Hollywood, the definitive biography of America’s favorite swashbuckler (she relays the full story below).

You have been a Fairbanks fan for a long time! How did you first discover your love of silent film, and more specifically, Douglas Fairbanks?

Lillian Gish was my gateway drug to silent films. I was in middle school, stuck at an airport with my parents due to a canceled flight. Thank heaven it was canceled; little twists like that can lead us to our fates. In my case it was the airport bookshop. At the top of a pile of paperbacks on the floor was a book with Lillian Gish’s lovely face staring at me. I convinced my mother to buy the book, and my fate was sealed. I became an avid fan of silent films, which was a challenging thing to be in the early 1970s. The films weren’t readily available. It wasn’t until I was in high school that I learned that you could buy 8mm prints from a company in Davenport, Iowa, called Blackhawk Films.

From that point forward, the cosmopolitan of Davenport became the center of my existence. I would iron clothes for a dollar an hour to be able to buy prints. Two reels ran about $15 in those days.

Among the films I purchased were several made by Douglas Fairbanks, both early in his career (the coat-and-tie comedies), and later, when he made swashbucklers. I had read about Fairbanks in a 1971 article written for American Heritage Magazine by Richard Schickel. I was so taken with it that I took it home from the library and retyped it, every word. (Guess I didn’t want to spend the money on a Xerox.) Fairbanks was a fascinating figure: so joyous a screen presence, but not a studio-produced product. He was the studio. He was so much more than an actor.

How did you discover the love letters between Fairbanks and Mary Pickford?

Ah, there is a story. The letters were in a little cardboard box, with a typewritten label:

PERSONAL AND PRIVATE

MISS PICKFORD

They were in the possession of Buddy Rogers, Mary Pickford’s last husband. I don’t think he ever bothered to look in the box, as I know for a fact that he destroyed other Fairbanks love letters when they were found after he hired people to clear out the Pickfair [Pickford-Fairbanks] attic in preparation for the 1980 auction of her estate. Upon his death, they went to his last wife. Upon her death, they, along with a wealth of all the good furniture and personal items he had held back from the 1980 auction, were left to her nieces.

But they had a problem. The will instructed them to fund a musical program for disadvantaged children. (Buddy, besides being a movie star, was a bandleader.) To fund the project, the nieces elected to sell Mary Pickford’s two Oscars.

The Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences took exception to this. Their stance was that no Oscar awarded after the late 1940s could be sold—the recipient was contractually obliged to sell it to the academy for ten dollars. Mary’s first Oscar was in 1929, but she received an honorary Oscar in the 1970s. Her signature on the form accepting this latter Oscar gave the academy rights to claim the earlier Oscar as well. Or so they said.

The family differed. And so they went to court. And lost. Lawyers cost money, alas, and the nieces were compelled to put a tremendous amount of Pickfair items up for auction. Jewels, furniture, dishes—you name it. And in the midst of this treasure trove was that little cardboard box.

The auctioneers looked inside, and knew what they had. They publicly identified the contents, and metaphorically speaking, the ears of every autograph dealer in the country perked up. They each wanted to buy the collection, break it up, and sell the letters individually. What could be better than a love letter from Douglas Fairbanks to Mary Pickford, when each was married to someone else?

I understand that dealers need to make a living, but this seemed to me to be a dreadful thing to happen. The letters belonged together, as a collection, I felt. In an archive, perhaps.

Perhaps my judgment was affected by the fact that I was recovering from major spine surgery. I was stuck in a reclining chair for twelve weeks, in a hard cervical brace, on— shall we say, heavy duty?—drugs. I was bound and determined: no one was going to break up those letters! So I bid. And bid. And bid. It was a little scary—they went for ten times the estimate. But I won them.

Then, once I had them came the question: what on earth to do with them? I could donate them to the Margaret Herrick Library, of course, where Fairbanks’s and Pickford’s papers reside. But not right away.

A dear friend suggested I put together a little photo book built around the letters. But I didn’t think that would work. The letters needed more context. “They could form the centerpiece of a good biography,” I said. “Fairbanks can use one. But that would take ten years.”

Then it occurred to me: those ten years would pass, whether I wrote a biography or not. Why not do it?

Aside from the letters, what other source material helped in your research for the book?

I tried to use primary source material as much as possible. Interviews with directors and lesser staffers exist in sundry books and archives. The challenge, of course, was to figure out when they were exaggerating. (Answer: almost always. Hollywood figures tend to create engaging fiction.) But digging deeper into various collections—the tax and legal records at the Herrick Library, the microfilm of the bookkeeper’s entries at the Triangle Collection at the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research—revealed a wealth of truth. And it was far more interesting than the fiction.

I also physically went to every place he had worked or lived. I walked the streets of Denver. True, his childhood homes (there were many) were all torn down, but neighboring surviving structures spoke volumes. I went to his studios—how else to discover the subterranean track for nude jogging? I stood in the room where he died and listened to the ocean from the window he faced.

I read the scripts for every play he performed in. They’ve been sitting, untouched, at the Library of Congress for a century. Most of his films were based on a book or a story: I read them all. It was instructive, how he would deviate from the script. And speaking of that, reading the film original scripts was also tremendous fun. You could see how the scenarist would write that Doug was to enter a building and pick up an umbrella from his sweetheart. But in the film, he doesn’t go through the door; he climbs up the side of the structure to meet her at the window. You got a sense of his loopy improvisational skills and his tremendous athleticism.

There are so many great anecdotes in your book about Fairbanks’s eccentricities—building that private running track so he could jog in the nude, for one. What were some of his other quirks?

He weighed himself twice a day. He was obsessive about having the right weight for the character. Robin Hood lived in a different era from D’Artagnan; he would be beefier. For The Thief of Bagdad, there wasn’t an ounce of fat on his form. He was all muscle.

And he was a tremendous clotheshorse. He had so many overcoats that his British tailor had to keep a scrapbook of all the fabrics so they didn’t repeat themselves.

In your book, you describe how pop culture is still rife with Fairbanks’ influence. What are a few of the ways in which we might see remembrances of Doug in today’s films, though we may not recognize him?

When you see Johnny Depp slide down the sail by slitting it with a knife in Pirates of the Caribbean, you are seeing a stunt that Fairbanks invented. When you see Fred Astaire dance on the walls and ceiling of a room in Royal Wedding, know that was taken directly from Fairbanks’s When the Clouds Roll By. (They used the same mechanism in shots of Leonardo DiCaprio’s Inception.) Whenever you see a character who combines the heroic with the humorous, you are seeing Fairbanks. When you see Batman or Superman, just remember that both were modeled on Doug. I could go on all day.

Why do you think mainstream history tends to forget Fairbanks and the strides he made for cinema?

Silent films as a whole are largely forgotten and disregarded. People remember Charlie Chaplin, and perhaps Buster Keaton. But little more. There is only so much that people can keep track of. If I were to ask you to identify a nineteenth century politician, you would likely remember Abraham Lincoln, but few would identify Williams Jennings Bryan. But he was a major figure to his contemporaries. And some folks, let’s face it, merit forgetting. But Fairbanks is not one of them.

It’s hard for such a devoted fan to choose just one, but if you could, what would you say is your favorite Fairbanks film?

It’s hard for such a devoted fan to choose just one, but if you could, what would you say is your favorite Fairbanks film?

Hmm. I’d have to say The Mark of Zorro. It is the perfect transitional film between his coat-and-tie comedies and the swashbuckler films of the twenties. It is pure joy, through and through. There’s another popular culture character that exists today because of Fairbanks.

If Fairbanks were alive today and you could ask him one question, what would it be?

Oh, heavens. I’ll be up all night trying to come up with a good answer to that one.

—compiled by Caitlin Eck

The First King of Hollywood was published October 1, 2015 and is available wherever books and e-books are sold, including our website.

Check out our previous post Evolution of a Cover: The First King of Hollywood.

No Comments

No comments yet.