As a journalist with more than 25 years of experience in the science and medicine fields, Luba Vikhanski has often reported on cutting-edge technologies and treatments for publications such as the New York Times and Nature Medicine. For the past decade, though, she’s investigated the century-old story of Nobel Prize winner Elie Metchnikoff, “the Father of Natural Immunity.” He’s best known for discovering phagocytes, the special white blood cells that digest foreign particles at sites of infection, and his work was the beginning of our current understanding of the body’s inherent defense systems. Along the way, he also pioneered the fields of gerontology and probiotics.

As a journalist with more than 25 years of experience in the science and medicine fields, Luba Vikhanski has often reported on cutting-edge technologies and treatments for publications such as the New York Times and Nature Medicine. For the past decade, though, she’s investigated the century-old story of Nobel Prize winner Elie Metchnikoff, “the Father of Natural Immunity.” He’s best known for discovering phagocytes, the special white blood cells that digest foreign particles at sites of infection, and his work was the beginning of our current understanding of the body’s inherent defense systems. Along the way, he also pioneered the fields of gerontology and probiotics.

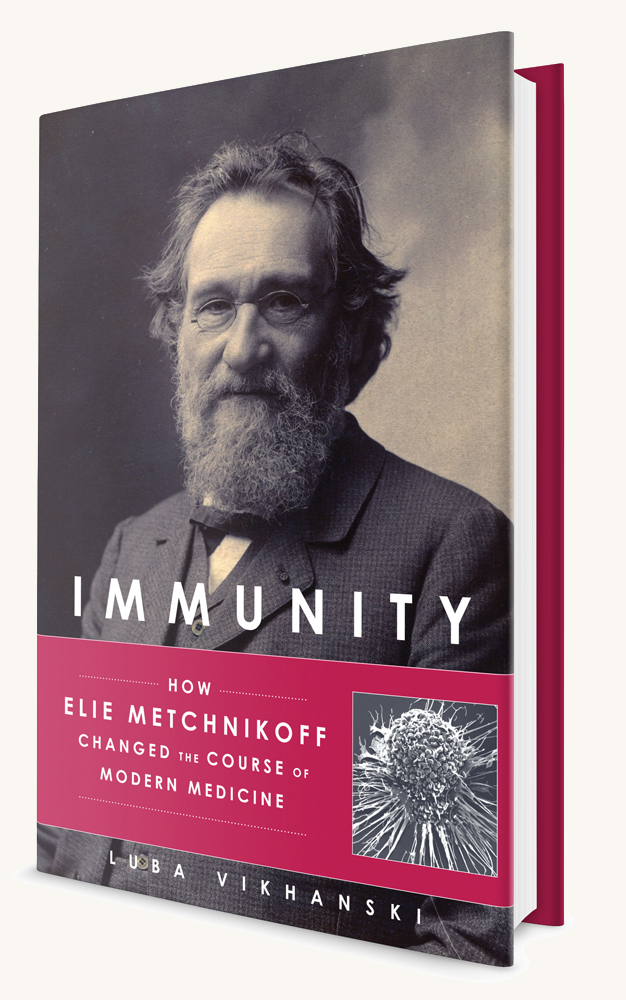

Vikhanski’s research into Methchnikoff’s life, including multiple fact-finding trips to France and Russia, visits to dozens of archives, and interviews with many current scientists, resulted in Immunity: How Elie Metchnikoff Changed the Course of Modern Medicine. Here, she discusses her detective work for the book in detail and explains how Metchnikoff’s ideas and insights remain relevant today.

You grew up in Russia and heard about Metchnikoff at an early age, but when did you decide you wanted to write a book about him?

When I was a teenager in Moscow, back in the 1970s, I resented the hero worship that was lavished by the Soviet regime upon great figures in Russia’s history, including Metchnikoff. I secretly suspected that their “greatness” was mainly a product of communist propaganda. So, some 30 years later, long after I’d left Russia, I was amazed to learn that Western immunologists indeed viewed Metchnikoff as a true hero of medicine. I decided to look into his life story—and found it fascinating. I also became convinced that such an important historic figure deserved a biography. It helped that I knew Russian and French, the languages of the two countries in which he lived.

Describe the overall research process for Immunity. How long did it take? Where did you begin?

There was no way I could have done proper research on Metchnikoff when the Soviet Union still existed. But now all restrictions on the use of archives and libraries by foreigners have been lifted in Russia, so I was able to work there freely. I even got access to a former KGB archive, where I found reports of the tsarist police spying on Metchnikoff. I began my research by collecting everything that had been published about him in Russian. All in all, the research and the writing took me about 10 years. During this time, I made three trips to Moscow and two trips to Paris, and I also visited Metchnikoff’s birthplace, near Kharkov; the Odessa university named after him; and the Naples Zoological Station, where he loved to work.

You spoke to a number of contemporary immunologists and gerontologists who helped you understand the science in the book. Were there any experts you found particularly helpful?

Dozens of researchers gave generously of their time, but perhaps the most fun interviews were with the two experts on aging, Steve Austad and S. Jay Olshansky, who’d made a bet, each wagering $150: Is a person living today going to reach the age of 150? Austad believes—as did Metchnikoff—that humans can indeed live to 150; Olshansky doesn’t think that’s possible. The offspring of the winning scientist will collect the prize in 2150. Despite their differences, both Austad and Olshansky spoke with great admiration about Metchnikoff as one of the early modern thinkers in the field of aging.

In the course of your research, you also came into possession of a trove of Metchnikoff’s papers that had been sealed in a bank vault in Paris for more than a decade. How did you find out about these papers? How did you get access to them?

Finding those papers was a biographer’s dream: no science historian had ever laid eyes on them! In 2007, on my way to New York, I’d made a stopover in Paris. There, I learned that Metchnikoff had a goddaughter, Lily, who, in fact, may have been his out-of-wedlock daughter. I was so intrigued that I launched an entire detective investigation. I eventually found out that a secret archive of Metchnikoff’s letters and other papers that Lily had preserved was locked up in safe-deposit boxes in a Parisian bank, on the Champs-Elysees, of all places. Luckily, I found a French lawyer, a friend of Lily’s late son, who managed to obtain for me permission to break into these safe-deposit boxes and make copies. This happened in 2012, so it’d taken me five years to gain access to these documents. They are still locked up in that bank. The Pasteur Institute is now trying to acquire them.

What was some of the most surprising information you were able to glean from the long-unseen documents?

I knew the letters might reveal that Metchnikoff had a secret love affair with Lily’s mother. So it wasn’t exactly a surprise when that was what they showed, but for me, as a biographer, this certainly was an exciting bit of information. Metchnikoff had no children with his wife. There’d been rumors that he had a love child, but these long-hidden letters enabled me to write about his love life while relying on evidence, not hearsay.

Metchnikoff had many character quirks, including a habit of boiling his fruit before eating it to make sure it was free of bacteria. Were there specific traits of his that you found especially interesting or unusual?

Metchnikoff was indeed obsessed with avoiding germs. When he invited guests to a restaurant, he asked waiters to bring to the table a special heater so that he could sterilize his own and his guests’ utensils. But quirks aside, I found particularly endearing his tendency to take people under his wing, caring for their health and daily needs, even when no one had asked him. Early in life, this trait earned him the nickname “Mamasha,” or “mommy”; in his later years, in Paris, students and others called him Papa Metchnikoff, or simply Papa Metch.

For all his accomplishments, Metchnikoff isn’t as recognized today as some of his peers, including Louis Pasteur, whom he worked with closely. Why do you think that is?

For all his accomplishments, Metchnikoff isn’t as recognized today as some of his peers, including Louis Pasteur, whom he worked with closely. Why do you think that is?

People tend to recognize the names of scientists whose work has a direct impact on their lives. Everyone knows about Pasteur because pasteurization saves us from drinking contaminated milk and Pasteur’s vaccines saved so many people from disease. Metchnikoff’s discoveries, by contrast, were for many decades considered medically useless. So, even though in 1911 he had been voted one of the 10 greatest people in the world, after his death in 1916, he was soon forgotten. But his name did continue to be recognized in connection with yogurt, which he thought might help delay aging. And I still come across his name in modern writings about yogurt. [NPR discussed Metchnikoff’s contributions last year as part of their “For the Love of Yogurt” features.]

What aspects of Metchnikoff’s work do you think people should be paying the most attention to now?

Immunologists I interviewed told me that thanks to the recent revival of interest in innate immunity, the study of which was pioneered by Metchnikoff, we can expect to see improved vaccines and new therapies for inflammatory and autoimmune diseases. Another thing to watch is cancer therapy; there has already been a small study targeting macrophages, the cells that Metchnikoff defined and named, in cancer patients. As for aging, it will be most interesting to see if strategies are developed in the future to improve people’s health by altering their intestinal microbes, as Metchnikoff suggested. There is also preliminary evidence that intestinal microbes might indeed affect aging itself, as he believed, though this impact is probably more complex than he ever imagined. These studies are still at their very beginning, but I’m sure we’ll be hearing more on this topic in the coming few years.

-compiled by Geoff George

Immunity officially publishes on April 1, 2016.

[Buy it now, $27] [Request a review copy]

“[An] outstanding, enlightening and delightful biography.” —The Jerusalem Post

“As Vikhanski richly illustrates, Metchnikoff did everything with passion, in both his professional and personal lives. A portrait that captures not only the man, but also the end-of-the-19th-century dynamism that fostered revolutions in art, politics, and science.” —Kirkus Reviews

No Comments

No comments yet.