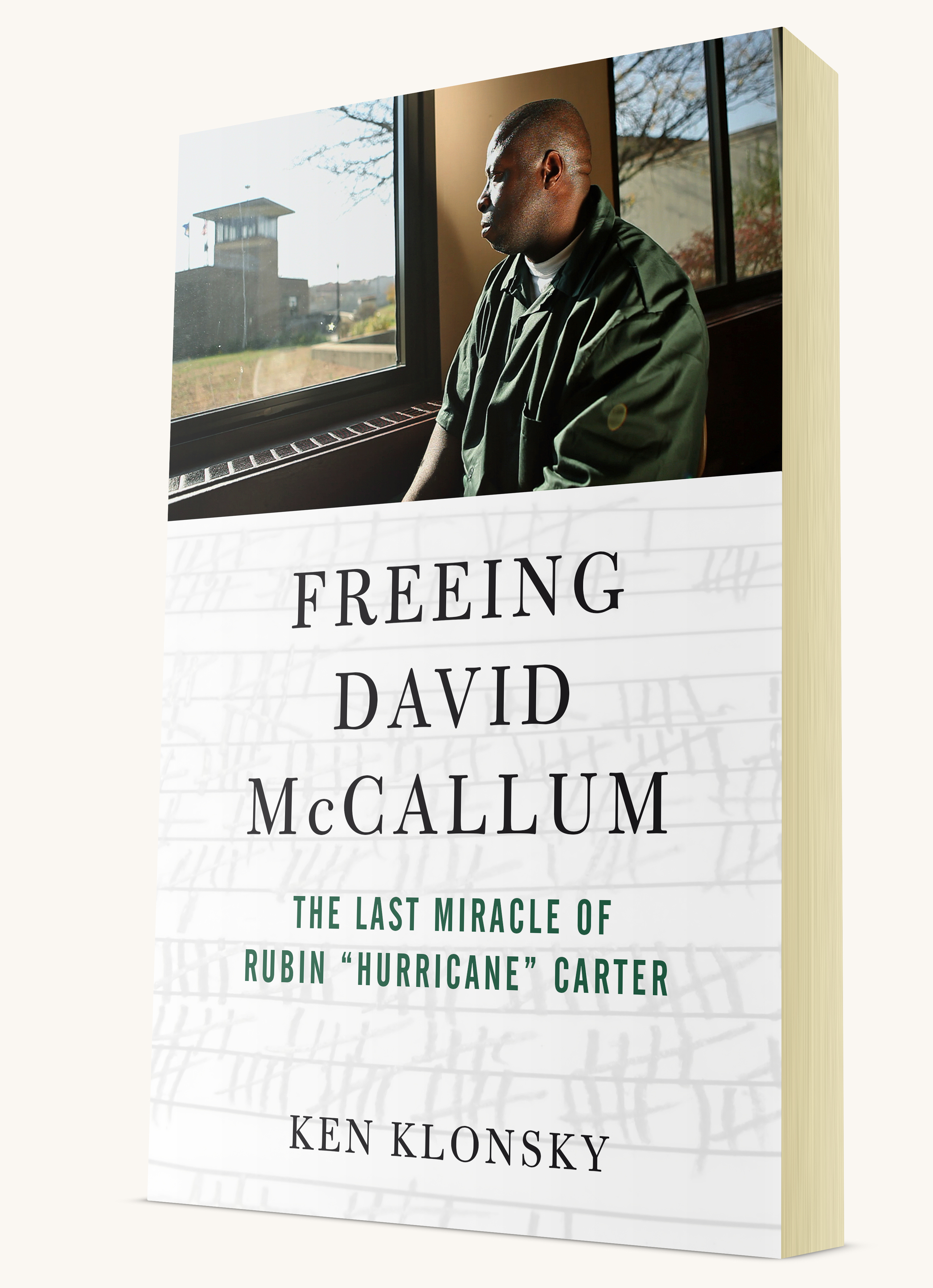

In 1985, David McCallum was wrongly charged with and ultimately convicted of the murder of Nathan Blenner in Brooklyn. David never lost the desire to prove his innocence. After writing over 600 letters, he finally reached legal advocate Ken Klonsky and legendary fighter Rubin “Hurricane” Carter, whose own wrongful conviction story captured the attention of Bob Dylan and Nelson Mandela. The advocacy team developed a steadfast loyalty to one another and, along with the help of friends from across North America, dedicated themselves to righting the wrong that had stolen 29 years of David’s life. Freeing David McCallum shares the story of three loyal friends and their allies who sought justice.

In 1985, David McCallum was wrongly charged with and ultimately convicted of the murder of Nathan Blenner in Brooklyn. David never lost the desire to prove his innocence. After writing over 600 letters, he finally reached legal advocate Ken Klonsky and legendary fighter Rubin “Hurricane” Carter, whose own wrongful conviction story captured the attention of Bob Dylan and Nelson Mandela. The advocacy team developed a steadfast loyalty to one another and, along with the help of friends from across North America, dedicated themselves to righting the wrong that had stolen 29 years of David’s life. Freeing David McCallum shares the story of three loyal friends and their allies who sought justice.

Author and wrongful conviction advocate Ken Klonsky talked to us about what it takes to survive and fight a wrongful conviction, and the relationships that make it all worthwhile.

Though the justice system created difficulties at every turn, David conveyed a calm wisdom and hopeful philosophy in his letters. Where do you think he drew his inner strength from?

David has said repeatedly that his strength was attributable to his severely disabled older sister, Ella, who was born without a spine and with cerebral palsy. Her mother was told that she wouldn’t live past 14 years of age and she’s well into her 50s now. This also tells me that David’s mother, Ernestine, is another source of strength.

David and Rubin seem to have such different personalities—David subdued and contemplative, Rubin bold and assertive—and yet they were kindred spirits. How did their wrongful convictions shape their relationship?

Rubin was a fierce and determined man who lived his life on rigid principles. If you ran afoul of him, he’d cut you off instantaneously, even lifetime friends and family. This tendency was attributable to his learning to be a law unto himself. When he was imprisoned, he spent ten years in total down a dark hole in solitary confinement because he refused to obey prison rules. He was not guilty, so he didn’t belong in prison, so he would give nothing to the prison and let nothing be taken away. His life after prison reflected this awful experience.

David was a model prisoner who survived by being positive and taking whatever advantages came his way. He was no less determined than Rubin to prove his innocence, but he went about it differently. He remains polite, humble and deferential. He tries to avoid trouble at every turn, just as he did inside the prison walls. The negative side of this is that he has difficulty with being autonomous, making decisions and so forth. But he does what he needs to do in the end.

What effect did Rubin’s New York Daily News op-ed have at such a crucial moment in the case?

Writing the op-ed, really a deathbed letter, was highly dramatic and heart wrenching. Such a plea from such a great man at such a time went right around the world. Ken Thompson surely read it (it was addressed to him as well) and put David’s case at the top of the list for the Conviction Review Unit. This was no small thing as the Brooklyn list exceeded 100 cases.

In 1985, police used incriminating and discriminatory tactics against David and his co-convicted, William Stuckey, to pressure them into false confessions. How does this play into our discussions on police brutality today?

Police brutality today is closely aligned to racism, as it was in 1985. Black suspects were routinely tortured in Chicago. African Americans are by far the greatest victims of wrongful convictions brought about by forced confessions. There is no shortage of racist attitudes everywhere in America right now, spurred on by an oblivious president who green-lighted police brutality in his ignorant statements about arresting suspects. It profoundly disgusts me that so many people would go along with it. It points to a deficient education, especially in law and history subjects.

You speak in the first two episodes of the Netflix documentary series The Confession Tapes to discuss your work with the True East case. How did you feel reflecting on film versus in writing?

Media, especially social media, has a greater effect than writing, simply because more people are attuned to it. But never underestimate the power of the written word; it is more lasting.

One major touchstone in the book and The Confession Tapes series is that many people have trouble understanding how or why the accused would give a false confession. Can you explain why this happens so often?

The younger the suspect or the more impaired, the more likely the false confession. BUT two reasons are paramount:

1. Young people want to get home as soon as possible and can be more easily manipulated if that carrot is dangled in front of them.

2. Many people are willing to talk to police and tell their stories without the presence of a lawyer. That is the single worst mistake a suspect can make.

Even if a lawyer is not present, you are not required to talk to police. Never believe that the truth or your innocence will protect you. The police will fit you into their possible scenarios and sometimes look no further.

What was the moment you felt closest to giving up? What was the moment you felt the most hopeful?

What was the moment you felt closest to giving up? What was the moment you felt the most hopeful?

I wanted to throw in the towel after Judge Firetog rejected our 440 Motion to attain a hearing. I thought that the system was arrayed against us. It was a “near death” experience.

When Ken Thompson was elected to the DA’s office, I knew David would be home before 2014 was out.

David developed a mentorship with your son, Ray. How did their relationship affect you as a father and as an advocate?

David essentially saved Ray from mindless, impulsive, angry behavior. How can anyone repay that? He fulfilled my request to such a degree that I would have to have died to give up his case. I accept David as Ray’s older brother. I also understand that a father’s role is limited in terms of advising sons or daughters. They are more inclined to listen to mentors.

What is the relationship between you and David like now?

I’d say that I maintain a role of acclimatizing David to the subtleties of everyday life. He, on the other hand, feeds my optimism and my belief that anything is possible if you stay the course.

What do you hope readers take away from Freeing David McCallum?

That is a hard question for a writer. One thing I’d like them to understand is that large goals dealing with massive systems and bureaucracies take years to accomplish and cannot be accomplished alone. People need to cooperate and work together and not care who gets the credit. Two cheers for unselfishness.

“After you read this gripping tale of a Brooklyn teenager coerced into falsely confessing and freed nearly thirty years later, you will not think about confession evidence or criminal investigations the same way.” —Brandon L. Garrett, author of End of Its Rope: How Killing the Death Penalty Can Revive Criminal Justice and Convicting the Innocent: Where Criminal Prosecutions Go Wrong

Freeing David McCallum: The Last Miracle of Rubin “Hurricane” Carter is available wherever books and e-books are sold.

[Order it now $17] [Request a review copy]

No Comments

No comments yet.