It’s been more than 25 years since the last biography of Nelson Algren came out, and Chicago journalist Mary Wisniewski spent about half that time crafting her own book on the famed author. In the evenings, on the weekends and between articles for her day job as a transit reporter for the Chicago Tribune, Wisniewski slowly found the time to dive deep into archives across the Midwest and to speak to friends of Algren’s who were still alive.

It’s been more than 25 years since the last biography of Nelson Algren came out, and Chicago journalist Mary Wisniewski spent about half that time crafting her own book on the famed author. In the evenings, on the weekends and between articles for her day job as a transit reporter for the Chicago Tribune, Wisniewski slowly found the time to dive deep into archives across the Midwest and to speak to friends of Algren’s who were still alive.

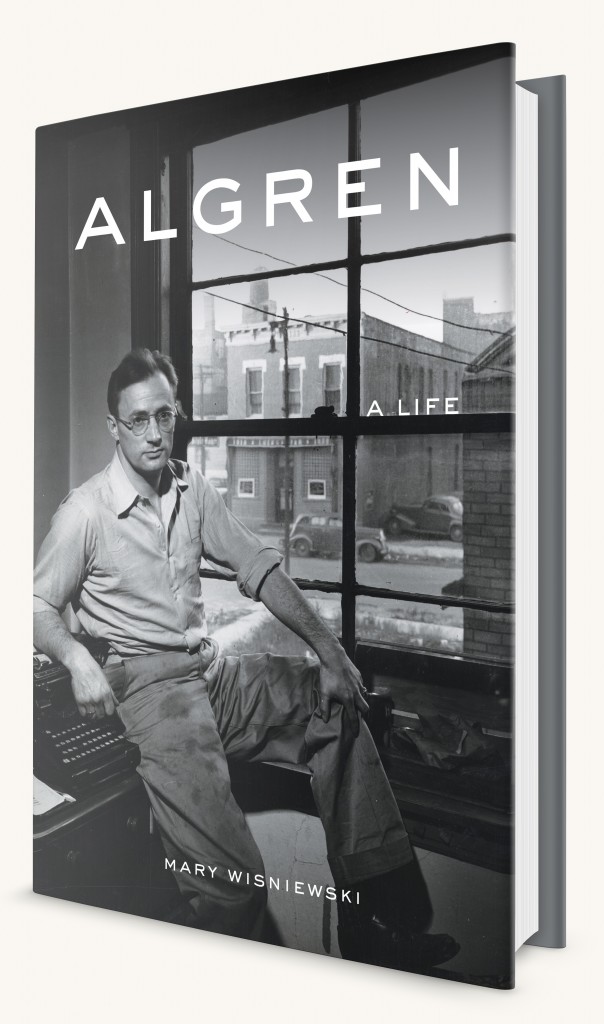

The fruit of her labors, Algren: A Life, will be published on October 1. In a starred review, Booklist says, “To tell the story of writer Nelson Algren’s baffling temperament, up-and-down life, and underappreciated work, a biographer needs to know Chicago, and city native and Chicago Tribune reporter Wisniewski has impeccable bona fides. Her descriptions of the struggling neighborhoods that shaped Algren’s piercing perception of the inequities of the world and inspired him to grapple with life’s grimmest aspects in his fiction are at once viscerally immediate and historically informed.” Here Wisniewski discusses her research efforts in detail, including her favorite interview subjects and the Algren homes and workplaces that she was able to visit in Chicago and elsewhere.

This is your first book. What inspired you to tackle Algren as a subject?

I was an English major but had never heard of Algren from my teachers. He wasn’t part of what’s considered the canon of American literature, like Hawthorne or Faulkner. I picked up The Man with the Golden Arm on my own at the college library and was startled by the beauty of the writing. I was also surprised by its setting in my family’s old neighborhood: Chicago’s Wicker Park. I had never thought of people who talked like my relatives as being worthy of literature. After that, I read every Algren book I could find. When I became a reporter in Chicago, I kept running into people who knew Algren and told me stories about him. I wanted to tell his story—why he chose to focus so keenly on the problems of the underclass, and how the city and the times inspired him.

You were able to use your reporting skills to actually track down and talk to a number of Algren’s good friends and acquaintances who were still alive, including photographer Art Shay and historian Studs Terkel. Was there anyone who was particularly tough to find?

Unfortunately, some people who knew Algren well have passed on, like his ex-wife Amanda, so I had to rely on letters and secondhand accounts for their perspectives. But many people he had known stayed active in literary and journalistic circles, so I found them through their websites or other people who knew them. One person who was a little hard to find was Fred Hogan, an investigator who helped in the eventual acquittal of Hurricane Carter and who had aided Algren in his research of the case. Fred had since become a leader on a New Jersey council on compulsive gambling. This is a little ironic, given Algren’s troubles with keeping away from the poker tables.

Who was your favorite person to talk to?

That’s hard to pick because Algren knew a lot of amazing people, so I’ll just give a few examples. I really enjoyed my talks with Dave and Doris Peltz, who loved Nelson but weren’t afraid to point out his flaws. Interviewing Studs Terkel was tricky because he was pretty deaf in his later years and I could not really ask follow-up questions. I just had to lob a question at him, big and slow like a 16-inch softball, and let him ramble on for as long as he wanted. Fortunately, my late father was the same way, so I had practice at that kind of interviewing. My very favorite interview subjects were my parents, who I questioned about the look and feel of the old neighborhood at the time Algren was writing. I quote my dad in the book; like some other area Poles, he wasn’t too impressed with Algren. He thought the people in Golden Arm were bums.

You clearly spent a lot of time conducting research in various archives, too, and you even uncovered some of the author’s previously unseen writing and correspondence. Where and how did you track down this material?

I did most of my research at Ohio State University, which has Algren’s archives, including many, many personal letters to and from friends and relatives. Algren was a packrat and kept things like the notebooks from his hobo journeys and his grade-school autograph book, which were really useful for piecing out his personality. I also did research at the Newberry Library in Chicago, which has an archive for Jack Conroy, a writer and longtime friend of Algren. This contained a lot of random material, including postcards Algren had exchanged with his mother. The Chicago History Museum was a source for radio interviews. Algren friends like Suzanne McNear also supplied me with correspondence. The lady who ran Algren’s estate sale gave me access to a big box of crumbling papers he had left behind. The research process involved a lot of sneezing.

What other archival resources did you find most valuable?

The Chicago Public Library has an Algren collection in their rare-books section, which includes magazines where his first stories appeared, first editions of his books, and many interviews and book reviews. Another big source was the US government, which had Algren’s military records—showing a lackluster career—and his FBI files. The FBI watched Algren very closely for about 30 years, and they kept track of political meetings he attended, protest letters he signed, and people he met. I obtained this material through a Freedom of Information Act request. It was creepy to see how the federal government kept tabs on a private citizen, but as a biographer, I found it terribly useful.

You live in Chicago, as Algren did. Do many of the major landmarks from his life in the city still exist? Did you visit them while writing?

Absolutely. I visited both city neighborhoods where he grew up, the places he frequented as an adult, and his homes in Gary, Indiana, and Sag Harbor, New York. The South Side Chicago house is gone, but the Albany Park two-flat is still there. I asked to go inside to see the layout of the rooms, but the friendly resident had big dogs and he wasn’t sure he could trust them. I went to Roosevelt High School, where the librarian let me look at the old yearbooks from the 1920s to find Algren’s pictures. The old police headquarters where Algren used to see the lineups is gone, but I used to work there as a City News reporter, and I remembered how crummy it was. Unfortunately, the place on Wabansia where he did some of his best work was mown down by the Kennedy Expressway.

Between the interviews and the archival work, approximately how long did you spend researching and putting this book together?

About 12 years, but with interruptions. I started formally interviewing people and doing research in 2004. It was tough to keep at it, though—I had a busy day job as a reporter. Also, life kept intervening—a new baby and some serious family illnesses made it difficult to work on the book for a while. It also took time to find a publisher. But I kept plugging away, finding new sources and new interview subjects. I also got a lot of encouragement from Algren friends and fans who wanted to see this happen.

About 12 years, but with interruptions. I started formally interviewing people and doing research in 2004. It was tough to keep at it, though—I had a busy day job as a reporter. Also, life kept intervening—a new baby and some serious family illnesses made it difficult to work on the book for a while. It also took time to find a publisher. But I kept plugging away, finding new sources and new interview subjects. I also got a lot of encouragement from Algren friends and fans who wanted to see this happen.

So you’re a big fan of Algren’s work personally, too, yes?

I’m an enormous fan. My main reason for writing this book is that I wanted more people to read Algren. I love The Man with the Golden Arm, The Neon Wilderness, Chicago: City on the Make, and Never Come Morning. I think his writing is poetic and unique, and his insights into the underclass are essential to understanding the shadow side of the American experience. I think this is the focus of most great American literature; artists like Mark Twain and Herman Melville and Gwendolyn Brooks wrote about outsiders. I have mixed feelings about other Algren books. Somebody in Boots is a powerful but flawed first novel. Even Algren admitted that it can be excessively violent. Walk on the Wild Side is funny but colder than his earlier work. I disliked his last book, The Devil’s Stocking. It has sections that are so bad they made me cry.

Which of the author’s novels would you recommend to someone who’s never picked up anything by him before?

If you’re a Chicago resident and you haven’t read Chicago: City on the Make yet, what the heck is the matter with you and go out and buy a copy right now! This is the book that helped define how Chicago talks about itself, as much as Carl Sandburg’s Chicago poems. Get the 60th anniversary version annotated by Bill Savage and David Schmittgens; that will help you through some of the old-timey slang. After that, I’d recommend the stories in The Neon Wilderness, especially “How the Devil Came Down Division Street,” and, of course, The Man with the Golden Arm, which deserves all the praise it gets. Don’t see the movies of Golden Arm or Wild Side, though. Their connection to the novels seems strictly coincidental.

-Geoff George

CHICAGO event: Mary Wisniewski will be discussing Algren at Volumes Bookcafe on Saturday, September 17 at 6:30pm, as part of Wicker Park and West Town’s Lit Fest.

Algren: A Life by Mary Wisniewski officially pubs October 1, 2016. It’s currently available wherever books and e-books are sold.

“Wisniewski reintroduces with fresh insight this signature American writer.” —Booklist, STARRED review

“It’s good to have the irascible, bohemian chronicler of the streets back via this top-notch biography.” —Kirkus Reviews

No Comments

No comments yet.